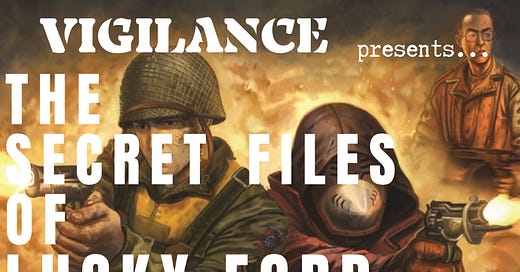

The Secret Files of Lucky Ford: The Butcher and the Black Tide, Part 3 of 13

Lucky Ford finds himself in the lair of the mysterious Gallo Rojo. But with the masked killer’s identity revealed, where does he, and his desperate rescue mission, fit into the chaos of volcano-choked Spain?

The Butcher and the Black Tide is now available as a Kindle ebook, in paperback, and as a DRM-free ebook.

This is Part 3 of The Secret Files of Lucky Ford, Mission 2: The Butcher and the Black Tide. If you haven’t read Part 1 or Part 2 yet, check them out before reading any further.

Content Warnings: Violence, Death, Gun Violence, Mild Swearing, Drug Use, Alcohol Use

MONDAY MORNING, JULY 12, 1943

EL GALLO ROJO’S REFUGE

THE SIERRA ESPUÑA MOUNTAINS, SPAIN

Emilia told her story slowly at first. She was uncertain where to begin, and searched her hideout for cues. Her eyes first settled on the battered chest plate and helmet she had been wearing when she'd rescued Lucky. She picked up the thick steel helm and became lost in it.

“You may have heard of my father, Eduardo Rosales,” she began quietly, her fathomless stare locked onto the dark recesses behind the helmet's eye slits. He hadn’t, but he didn’t interrupt.

“At our home, he kept a hall of armor just like this. He taught us about the history of each of the knights who had worn them, of their battles and their families. My father, though he always looked to the future, insisted we learn history, and of the people who directed its course.”

Her voice wavered, and she paused long enough to change the subject from her father and shift her green eyes back up to Lucky. She handed him the helmet. He turned it over in his hands while she spoke.

“The people call me the Gallo Rojo. They say this looks like the beak of a rooster. It is funny. In England, they think it looks like the nose of a dog. There, this type of helm is called the hounskull.”

The helmet was heavier than Lucky thought it would be. It was solid steel and seemingly impenetrable. He lifted the visor up and looked inside its long, pointed snout. Emilia'd mounted a small metal can inside, hollow save for thin tin sheets that would vibrate to distort her voice. That answered one of his questions, at least.

Lucky handed the heavy helmet back to Emilia. She was quiet for a moment, staring into the empty shell.

“My father taught us that people do not become great by what they accomplish for themselves, but by what they do for those around them.” She set the helmet down picked up her engraved chest plate. While she spoke, she ran her fingertips across the bullet dings and shrapnel scars. Lucky could hear old pain edge into her voice when she spoke of her father. “My brother and I tried to do that when we ran here. Tried to protect the people, let them live free of the war and all the evil that came with it.”

She sat silent for a moment.

“The Gallo was my brother's idea, at first,” she said. Lucky glanced over her shoulder and studied the suit of armor with the massive puncture in its center.

“When the war ended, Berto and I thought we'd have peace. Our family had no friends left, the Francoists saw to that, there was no way to get our old lives back. So we gathered all this, these worthless treasures, and escaped here. No more soldiers, no more fighting, this forest for a sanctuary. And it was true, for a time,” she said. She looked over her pistols, both still crusted with blood.

“We tried to live a quiet life here, only going into town to trade these baubles for food. But after a few months, people began disappearing from the villages. At first just drunks, philanderers, rebellious youths, people they expected to run off in the night. Then whole families. Houses emptied. Our father taught us to be brave, curious, and conscientious. Berto and I began going out at night to learn what was happening. We caught the bolseteros in action and scared them off. We saved a family not far from here. Then we did what Rosales always do: we planned, we designed, and we built.”

Emilia’s cave featured more tools than Lucky could name, with gun parts piled like discarded chicken bones.

“The next time we found them, we wore armor, we had weapons, we disabled their trucks and sent them running. In the villages, the legend of el Gallo Rojo and the bag-men began. But, no matter how many we saved, they took more every night.” She found a cloth and began wiping her bayonets clean.

“Our creations, like this, would rout any true army,” she said. She set her pistols down and retrieved a glass jar from her jacket pocket. Lucky took it it. She added: “These bolseteros are more afraid of their master than of what we would do to them.”

Lucky held the jar up to the candlelight to examine it. It was packed tight with white powder. She’d poked a small fuse through the brass screw-on top. He gripped the lid to unscrew it but Emilia snatched it away from him.

“Do not open that! You would blind us for a week!” she said, and snatched the jar away from him. “Berto, my brother, invented this. If not for the war, he would have designed wells like our father. Instead, he had to make weapons. Esto es una bomba de pimienta. Break it and you will cough and cry for days.”

Lucky tried his hand at translating again. Pimienta meant some kind of pepper. A pepper bomb.

“Is that why the bolseteros wear those masks?” he asked. She smirked, gorgeous, murderous, and mischievous in the flickering lamplight.

“And to cover their gas scars,” she answered, slipping the jar back under the tarp.

“They got gassed? By who?” Luck asked.

“The Nazis, of course,” Emilia answered. “Years ago, but all of them are still suffering.”

“Jesus,” Lucky said. The Colonel had mentioned that Department Three had operated as if the Spanish Civil War was a proving ground for their horrific experiments and a practice war for their officers.

“That is why they are here. The gas drove them mad. They killed women and mutilated themselves. The army had to round them up. They were kept in the old asylum until la Medida took them. Now they are bound to him.”

“They're coerced,” Lucky realized aloud. The Romanian was controlling these men, not with money but with their illness.

“Coerced, but malicious,” she answered. “They do deserve understanding, but never mercy.”

Lucky sat in silence, studying the floor.

“We could not save everyone. Berto was frustrated, and furious. After months hunting them from the shadows, striking when we had the advantage, he attacked them in full daylight. He knew what would happen, he must have. So he left me here, in this cave of worthless treasures.” Her green eyes danced between the stacks of paintings, the hand-crafted furniture, and the chests of heirlooms.

“I found him nailed to a cross three days later, on the side of the road for all to see. Espada had killed him to send a message, butchered him like a steer. But he did not know there were two of us.”

Her hands were clenched so tight that she could’ve ground stone to dust in her palms.

“I killed my first bolsetero retrieving my brother’s body. I killed my eighth that same night. I would have had Espada too, were he able to die. The Russians could not do it, I should not have expected to.”

“Who is he? None of my intel mentioned him.” Lucky asked.

“El Capitán Armando Espada, la Medida's right hand. The man behind the kidnappings, slave-driver to the bolseteros. A Falangist and attack dog for Nazis. He fought for them in Stalingrad before he lost his eye. His military connections earned him command of this region, and he is why none of Franco's forces disturb la Medida..”

“What about O'Laughlin?” Lucky wondered.

“For the first six months after Berto died, Espada had his bolseteros hunting me. They came close, yes, but those that did, died. Before today I had killed over sixty of them, more than one sixth of what Berto thought their numbers to be.” A morbid smirk curled the corner of her mouth. “O'Laughlin is new. Two months. He has come closest. They were chasing me in the woods tonight, you know. You fell into the middle of it. The Irishman might have caught me if you had not distracted him.”

“You're welcome, Miss Rosales,” Lucky said. He tried not to wince at the thought of the deep bruises the tree had hammered into his legs and back while creating that distraction.

“I think la Medida has become weary with my successes. O'Laughlin is here to finish Espada's hunt.”

She caught a stray lock of hair and pushed it back behind her ear. Lucky couldn't help but imagine himself doing that for her, staring into her emerald eyes. Her look jumped back from her dented armor to Lucky, almost knocking him off his seat when he realized she had caught his stare. A bit of a smile turned the corners of her mouth upward as Lucky fumbled to pretend he was looking elsewhere, but she had him.

She couldn't be more than a year or two older than him, but she had been living out there for years, making day-to-day survival and battle her entire life. She had dedicated herself to helping others, only to have that ripped away and replaced with a quest for vengeance. Her compassion had been warped into fury.

Emilia was split between lethality and grace. The Gallo Rojo would happily kill with bullet and blade, with flame and bombs. She’d killed over sixty people herself. But Emilia was wise, patient, and kind. Unfortunately, the world she lived in no longer counted those qualities as strengths.

“O'Laughlin said he knew your friends, the Unusual Occurrences,” she said, questioning Lucky without asking, just stating a fact. She was not accusing him or the Office of anything, but she wasn't far from it.

“I don't know anything about that, but the others might.”

“Your comrades in the forest?” she asked. “The bolseteros should have gathered their dead and retreated back to the batería, and the Irishman and his dog will retire for their afternoon cervezas, then come out again at nightfall. The afternoon will be our time, and it will be easy with this strange weather.”

Lucky agreed with her logic. The falling ash had made noon as dark as twilight. Vesuvius would cover their movement as they searched the soot-choked forest for Bucket and Miller. Soot, stone, and the cremated remains of hundreds of thousands of Italians would hide them from their hunters.

“How will we find anything in that mess?” Lucky asked her.

“If they are trained soldiers, it will be easy,” she said. She removed her heavy combat boots. Their bolted-on steel toes had been stained black by mud and coagulated ash. “They will have attempted to track you, will have found your parachute in the tree, and, if they are good, they will have avoided O'Laughlin and the Portuguese.”

She emptied a canteen into an ornate porcelain bowl and splashed water onto her face, washing away the grit and sweat from her skin. Despite having watched her take down eight armed mercenaries in brutal hand-to-hand combat as the Gallo Rojo, Lucky found it hard to imagine her even raising her voice.

“Wash and rest, Lucky,” she said. She wiped her face and looked up at him. Lucky suddenly felt like he had an inch of grime on him, and took the bowl from her outstretched hand. The water went gray the instant he touched it.

“Your comrades will be easy to find, though we must hope that we are the only ones out there who know to look,” she said.

As the thick layers of sweat-caked grit dissolved from Lucky's skin, comfort and exhaustion washed over his whole body. He had slept less than nine of the past seventy-two insane hours, and he suddenly felt every second of them. He could barely put a sentence together.

“I think,” he tried, grasping feebly for the words, “I think I may have a rest.”

Emilia said something, then pointed to the empty cot in the corner, but Lucky didn't hear her. He was already curled up, dead asleep with a munitions crate for a bed and his steel-pot helmet for a pillow.

MONDAY AFTERNOON, JULY 11, 1943

EL GALLO ROJO’S REFUGE

THE SIERRA ESPUÑA MOUNTAINS, SPAIN

Lucky woke with a start. He was dead tired, but days of paranoia, terror, and bloody combat left his senses alert for anything that could happen, even the cheerful tinkling of a tiny bell.

He rolled onto his side, grasping for his Garand. His hand passed through empty air. He creaked his eyes open. A dark, hooded figure with a grotesque metal face was standing over him, a bladed revolver in each gloved hand.

“Whoa!” Lucky yelped. He fell off the wooden crate that had been his bed and hit the floor, hard. Lucky had forgotten where he was, and seeing Emilia decked out in her gear before his mind caught up had knocked him on his can. He sat up, rubbing his jolted knee.

“Emilia,” Lucky said slowly, “What are you doing?”

“They are here,” she grated, her voice once again warped by the metal can in her helmet. “The bell means the stone moved.”

She was talking about the huge rolling boulder that concealed the tunnel's entrance.

“You got to have a back way out,” he said, hastily looking around for his rifle again before remembering that he'd lost it during the jump.

“Claro qué si.” 'Of course,' she said. “But I need to see who tracked me. If the Irishman is good enough to find me here and survive the tunnel, it changes where we can run to next.”

Lucky knew 'survive' meant whatever booby traps she had waiting for intruders.

“We can listen from here,” she said, then shoved a rack of exquisite dresses aside to reveal three capped pipes sticking out of the dirt wall. She held one gloved finger up to her helmet's 'beak' to shut Lucky's trap then gently unscrewed the first pipe cap and leaned in to listen. She shook her head, then motioned Lucky over.

He picked his way through the clutter and put his ear up to the pipe. Lucky couldn't hear anything but a few echoing drips and the whistle of hot wind across the open entrance of the tunnel. He looked back to Emilia and shrugged.

“If they are inside,” she muttered. “They will find the navajas soon...”

She trailed off and second tiny bell rang, followed by a loud snap that reverberated through the pipe. It sounded like somebody had just broken the suspension of an overloaded truck. The snap was followed in the same instant by the wet thunk of a busy butcher separating ribs with a cleaver.

“Holy shit!” someone yelled with a Brooklyn accent Lucky knew that voice.

“What the hell was that?” Bucket was shouting. “Miller?”

“We stopped them, now we finish them,” Emilia whispered. She held a cord in her hand, running through yet another pipe buried in the wall. She gripped the end tight, ready to pull.

“Wait!” Lucky shouted. He lunged at Emilia and grabbed her arm before she could trigger her trap.

“Do not touch me,” she droned. Her free hand was inside her jacket, no doubt wrapped around the grip of some terrible weapon. He let go and backed off, raising his hands.

“Those are my friends,” Lucky told her. “Let me out there, please.”

Emilia twisted away from him and nodded to the heavy oak door.

“Go to them,” she said, her helmet masking any wayward compassion in her voice. The rope stayed in her hand. “I will be listening.”

Lucky didn't wait for her to finish. He leapt over the crates and dodged around stacks of treasures, sprinting to the door. He racked open four giant bolts and gasped at its weight as he struggled to pull it open. The old hinges groaned and lamplight spilled into the dank tunnel, staining its walls and puddles yellow. He could see movement at the far end, a pair of blue flashlights illuminating two men, one kneeling, the other fallen.

Tripwires caught the yellow glow, like golden spiderwebs that crisscrossed the tunnel. Lucky carefully worked his way over each one, finally reaching Miller's side where Bucket was crouched over him.

“What the hell? Lucky?” Bucket asked. He flashlight reflected blue off his Coke-bottle glasses. Miller, on the ground, was still. “We finally track your white ass down, and Miller catches a shiv in the chest for our trouble!”

Bucket's voice echoed through the tunnel. He was angry, his face twisted up with exhaustion, confusion, and exasperation. Lucky looked down. Miller was splayed out in the mud, a huge knife buried deep in his chest, right below his left collar bone. Cold air rushed out through the wide cut in his suit, past the knife’s quivering ivory handle. Several other blades were embedded deep in the tunnel wall around where he'd been standing. Only their handles stuck out of the black mud.

“Private Ford, is that you?” Miller whispered from the floor. His voice was weak.

“Yes, Miller, I'm here,” Lucky answered. He dropped to a knee by Miller's side, taking the fallen man's gloved hand in his own. His knee sunk into the floor and greasy, sticky mud bled through his trouser leg. That close to the ground, the bacon smell was almost overpowering. Lucky pushed the thought from his mind and focused on Miller.

“I need you to do something for me,” Miller said. He coughed once, feebly.

“Anything,” Lucky replied. The carved, inlaid ivory handle wobbled as Miller tried to breathe. It was an heirloom chef's knife, which meant that about eight inches of blade had penetrated. Any other man would be dead in moments, if not already. Miller feebly gripped Lucky's forearm, staring at him through his gas mask lenses with ice-blue eyes.

Miller winked and said:

“I need you to pull this bloody knife out of my chest, it is quite uncomfortable.”

Miller wasn't any man. He lived in an ice-box, wore a thirty-thousand dollar freezer suit, and could take a Nazi sword straight through the heart. He winked at Lucky: this didn't hurt, it was business as usual.

Lucky did not understand Miller's sense of humor. He shook his head, then reached down, grabbed the handle, and put his other hand on Miller's shoulder to brace himself before he pulled the blade out like a ripcord.

“Hold on there, pal!” Bucket said. He grabbed Lucky's wrist to stop him. “You'll need this.”

Bucket handed him a roll of olive-drab hurricane tape. Lucky tore a piece off the roll with his teeth, just like he had when Miller had gotten himself stabbed back in Vesuvius.

Lucky took a deep breath, grabbed the knife handle, then paused. Miller looked out at him with his pale blue eyes through his gas mask lenses. He gave a gentle nod, and closed his eyes as Lucky began the excruciating process of removing the knife.

All eight inches of its dull edge scraped against Miller’s collar bone as Lucky dragged the steel from his chest. That little extra tug from the bone triggered a wave of nausea, but the knife came free. Lucky fought down his bile right as a blast of wet, freezing air from the hole in Miller's suit to blasted him in the face. Quick as he could, before Miller lost any more cold, Lucky planted the tape over the tear, made sure there were no leaks, then collapsed into the weird-smelling mud next to him.

“My thanks, Private Ford,” Miller said in his vaguely-English accent, always addressing Lucky by his proper title. “That was quite uncomfortable, but, to get caught in such a trap, one might rightly call me a 'boob.'”

Miller sat up and inspected Lucky's tape-job, then got to his feet. Bucket was already standing, examining the trap in the wall.

“She's damn ugly, and I wouldn't brag about her to my friends, but she she gets the job done,” he said quietly, then stepped aside so Lucky could see what he was so impressed with.

Emilia's blade trap had been perfectly hidden in the earthen wall, but now that it was sprung, looked every bit as improvised, deceptive, and deadly as the rest of her armory. The trap was built from a series of old flat springs that Emilia had flexed back into the wall. When Miller had run into the tripwire, the springs snapped out, each catapulting a butcher's knife across the tunnel's breadth.

“Quite clever, I have to admit,” Miller observed, still gathering himself from getting laid out by the high-velocity metal. He ran a hand across the tape holding in the freezing air provided by his suit, just a few inches above the tape Lucky had applied after Werner von Werner's sword had pierced his heart.

Lucky still had no idea who, or what, Miller was. Had he already healed from the knife wound? Did he even get hurt in the first place? Was he even alive? Miller's ears must have been burning, because he interrupted Lucky's thoughts:

“Now who might our gracious host be?”

Bucket cleared his throat, clipped his flashlight to his gear, and raised his hands in the air.

“I think we're about to get introduced,” he whispered

Lucky looked back down the tunnel in the direction of the yellow glow of Emilia's saferoom to find her standing before them, fully-armored, aiming down the barrel of the largest gun Lucky had ever seen in human hands.

It was a colossal shotgun, with a barrel three inches across, easy, and damn-near twelve feet long. Lucky had no doubt that the recoil alone would break someone in half, and he didn't want to consider what anyone on its business end would turn into. She balanced the monstrosity of a weapon on a huge bipod with a set of skids that she’d pushed through the mud.

“Yes, introduce us,” she said. “After seeing that performance, I will need more than names.”

Her gentle voice was twisted by the menacing mechanical filter in her mask. She braced both feet in the muddy floor and cocked back the hammer on her massive gun.

The sheriff had shown Lucky pictures of guns like Emilia’s back in Indiana. He’d called them ‘punt guns,’ and said that they could down an entire flock of ducks with a single blast. These kind of guns killed so many birds so fast that Congress had to outlaw them about forty years back. Backwoods hunters still liked to use them and the sheriff would have to confiscate the huge guns and melt them down. The things were so big and heavy that the hunters couldn't carry them; instead they'd mount them on rowboats and blast the birds out of the water. The recoil would throw the whole boat halfway across a lake.

“Emilia,” Lucky said, turning around to face her, hands empty and out ahead of him.

“Do not use that name,” the Gallo Rojo growled through her voice filter. All of the tenderness that Emilia had displayed earlier was gone.

“Emilia,” Lucky said again, “These are my friends, the ones I told you about.”

She didn't lower the punt gun, but she didn't turn them all into chili, either.

“This is Sergeant Bucket Hall. He's American, too,” Lucky said. Bucket stared Emilia down through his thick glasses, and she did the same to him behind her helmet, unflinching. Her finger eased off the trigger.

Miller carefully picked himself out of the mud behind Bucket, careful not to spook Emilia. His breathing had returned to normal after the knife attack, strong through his gas mask's filter. He placed his hand on Bucket's shoulder and stepped around him. The weak light escaping from Emilia's open strongroom door lit up the icy blue eyes behind those lenses.

“And this is...” Lucky tried. A loud splat interrupted his introduction. Emilia had dropped the punt gun’s butt to the muddy floor. She stood dumb-founded, her arms limp at her sides.

“Señor Miller?” she asked, almost whispering.

“Excuse me?” Miller started, obviously as surprised as Lucky was that this helmeted warrior knew his name.

Emilia threw back her crimson hood, then undid the latches of her helmet. Her helmet split open with a creak and her raven-black hair tumbled past her shoulders. She dropped the helmet into the mud next to her gun. Her eyes seemed to glow in the tunnel's gloom, luminous and verdant.

“Emmy?” Miller asked. He dropped the knife he'd been concealing behind his back, the one Lucky had just removed from his chest. It stuck in the soft floor, point down. Lucky hadn't noticed him pick it up, much less ready it for a potential attack. Sticky mud sucked at Emilia's boots as she rushed past Lucky and Bucket to wrap Miller up in a hug.

“Where did you go?” she asked, her face buried in Miller's chest. “My father...”

She started to sob. Miller put his arms around her, the shock of her embrace finally subsiding. He stroked her shining hair with his glove as she cried.

“I always meant to come back and see you, Emmy,” he said quietly. “The world moved too fast.”

“My parents...” she sobbed again. It was shocking to see a woman as tough as Emilia Rosales cry. Bucket and Lucky's jaws were hanging halfway to the floor.

“I heard, and I'm so sorry,” Miller said, trying to comfort her. “After we received news about them, I feared the worst for you and Berto. I thought you were... I'm so sorry, Emmy. Had I only known...”

“We ran here after... we tried to make a difference here,” she responded, some of the hard edge returning to her voice as she let go of Miller and took a step back. “We have helped here more than we ever could back home. But Berto...”

“Eduardo would be proud of both of you,” Miller assured her.

“Hold up a second here,” Bucket had finally recovered from the shock of Miller and Emilia's apparent reunion enough to speak up. “That guy's a dame?”

“Ah, Sergeant Hall, how rude of me,” Miller said, some of the composure returning to his voice. “This is Miss Emilia Rosales, daughter of a great friend to the Office, Doctor Eduardo Rosales.”

“Well hey now, I've heard of him,” Bucket said. “Good to meet you, miss. And don't mind Miller here, everybody else just calls me Bucket.”

“Emilia,” she said, flashing her smile and taking Bucket's extended hand, “No one has called me Emmy in many years.”

She let Bucket's hand drop from her own, then stepped past Lucky and scooped her helmet out of the mud.

“Come to my home, we have much to talk about.” Emilia led them back to her safe room. She danced over the tripwires with memorized precision. Miller followed closely, then Lucky, with Bucket right behind, still shocked to find Emilia behind that mask. The punt gun stayed behind, settled into the muddy floor.

It took Lucky a second to readjust to the lamp-lit cave, but Emilia wasted no time locking down her hideout. She pulled a hidden lever and a familiar bell jingled again, indicating the boulder entrance to her tunnel was rolling, sealing shut against further intruders.

Miller began wiping the sticky black-brown mud from his boots and uniform, while Bucket and Lucky took a seat on the stacked munitions crates. Emilia threw her red coat over the back of an opulent, velvet-cushioned chair, then hung her helmet off the end of its gilded armrest.

She casually drew one of her revolvers and dug the tip of its attached bayonet into the cork of a dusty wine bottle. Lucky's mouth watered; he hadn't had a lick of anything but warm canteen water in close to a week. The bottle's label was water-stained and peeling, but he didn't give a damn what it was. If it didn't taste like sweat, tin, and backwash, he was thirsty for it. Emilia drew the old bottle to her lips, then stopped as she noticed the three officials watching her.

“Lo siento,” she said sheepishly. She set the bottle down and jumped to her feet to search through another pile of crates. “It has been a long time since I have had company here.”

She smiled when she found one small case buried in the stack, then sat down across from Lucky and Bucket with it in her lap. She used her bayonet to pry it open, then set her bladed revolver aside.

Emilia carefully removed four crystal champagne flutes from their packing straw and blew the dust out of them. A splash of the white wine went into each glass. She took one and nodded to the officials; Bucket and Lucky each took one. Miller shook his head when she held out the last one for him.

“None for me, I'm afraid,” Miller said, politely declining the drink.

“No, I forgot,” Emilia gasped, embarrassed. “Sorry.”

“No, no, don't worry about that. More for you three.”

“Yes,” Emilia answered, pausing for a just second before dumping the contents of Miller's glass into her own. “Is there anything I can get for you?”

“Just a little privacy. I'm afraid it is time for me to sit and recharge for the afternoon.”

“Of course. There are more chairs in the back corner,” Emilia said, indicating a semi-clear area past a stack of weathered chests.

“Thank you, Miss Emilia,” Miller said. He unbuttoned his canteen pouch as he walked away, removing a strange device from it. Lucky only caught a glimpse of it, and all he could determine was that it was certainly not a canteen. It was a small silver cylinder with wires coming out of one end, a wooden crank handle on the other, and a few buttons and switches on its side. Lucky didn't have time to figure out what it was before Emilia lifted her glass.

“Salud.” Emilia toasted.

“Salud,” Lucky tried to say, stumbling over the new word.

“Damn right,” Bucket said. He and Lucky gently tipped their glasses back to sip on the old wine. Emilia just smiled and threw her entire glass back like a double shot.

The wine burned when it hit Lucky's mouth. It tasted like poison, like the strongest liquor he'd ever had. His eyes teared up instantly and he started coughing. Bucket wasn't faring much better, and he spit the vile liquid onto the dirt floor.

“What the hell kind of wine is that?” Bucket asked, grimacing at the horrible taste still lingering in his mouth. Lucky was still coughing, afraid he might get sick in front of her.

“Wine?” Emilia asked, confused, then her eyes gleamed with mischievous realization. She grinned wide and let out a hearty laugh: “No, oh no, this is orujo, grape liquor. Never let it touch your tongue.”

“Well in that case, it's delicious,” Bucket answered slowly, rubbing the toe of his boot in his spit to grind it into the dirt. He took a deep breath, let it out, then threw the whole glass back, downing the rest of the orujo. “Tastes like antifreeze: kind of sweet, and it gives your brain those lightning bolts.”

“Orujo was my father's favorite drink, so there are many more cases here,” Emilia explained. She poured another shot for herself and Bucket. “If it is too strong for you, Lucky, it is fine. We can add water.”

There was no way Lucky was going to chicken out in front of her. He threw the rest of the glass of disgusting hooch back. It burned all the way down. He screwed his eyelids shut against the automatic tears, and shook his head hard enough to dislodge the starbursts from behind his vision. Lucky took a deep breath and opened his eyes.

“I love it,” he rasped. “Tastes great...”

She smiled like she knew he was just trying to impress her. Then she reached for his glass with the bottle of vile brew in hand, ready to give him a refill.

“No!” he said with a start, yanking the glass out of her reach. “I mean, no thank you, that's enough for me.”

“Well then, that leaves just enough of the stuff for me and Miss Emilia here to have a good old time,” Bucket said, laughing. He took another slug of the orujo. Emilia smiled, then knocked hers back too.

“How do you know Miller anyway?” Lucky asked, hoping to distract her from his having nearly upchucked from one sip of the hooch that she could drink like water.

“Yeah,” Bucket said, smacking his lips to try to air out the orujo’s harsh after-taste, “Not too many people get to meet the snowman.”

Emilia set her glass aside and re-corked the bottle.

“Through my father. He was an inventor, he could make a machine to do anything he asked.”

“I remember reading about him when I was a kid,” Bucket said. “He won a bunch of prizes for his work.”

“He was the best. He wanted to use his inventions to help people everywhere. A good man, a 'citizen of the world.' During a lecture tour, he met Señor Miller in England.” Lucky looked back and tried to spot Miller between all the clutter, but couldn't see him from where they were sitting. There was a strange, pulsating buzz coming from where Lucky thought he had gone, but nothing identifiable.

“I must have been just six when my father built the freezer,” she remembered. “He wouldn't tell us why he was building it, but it was the largest in Spain when it was finished. Not just Salamanca, but in the whole country. My father's friends in England paid for the whole thing, thousands and thousands of pesetas.”

Lucky remembered that Miller's bunk on the Saint George was as cold as an icebox as well, just like the inside of his suit. Emilia continued:

“Not a week after it was finished, Miller came.”

“The spring of 1925, I believe,” Miller said, appearing out of nowhere.

“Oh, Señor Miller,” Emilia said, more surprised that he had been able to sneak up on her than anything else, “I had forgotten how quiet you can be. They were asking about you.”

“It is quite all right, Emmy. These gentlemen and I have been through quite a bit, and as such I had been meaning to share more about myself anyway,” Miller said, then took a seat next to Emilia, winking at Lucky and Bucket. “And I am sure they would rather hear it from you than a muddy relic such as myself.”

Bucket agreed enthusiastically. Miller grinned with his eyes, and Emilia flashed that smile again and resumed her story:

“I remember that day clearly, though I was young. One morning, before the sun was up, my father took us to the train station. A train of only five cars was already there, waiting for us. The engine, two cars of British soldiers, a caboose, and a meat car.”

Miller interrupted:

“Gentlemen, it was a refrigerated car in the style they use to carry perishable goods into the city. There was not, by any means, any sort of meats in it that day.”

Emilia chuckled and patted him on the arm.

“You always said that, but you smelled like sausages for a month!” she laughed, then continued. “The soldiers rushed one man out of the meat car and into the back of an ice truck, then escorted him back to our house. He went straight into our new freezer, then they locked it shut and guarded it like the Bastille. I didn't get a look at him for a week! Not until I figured out how to get in, when I watched him and my father working on this suit.”

Emilia ran her hand across the heavy seams of Miller's canvas, leather, and rubber coverall suit.

“Your father designed the environment suit?” Lucky asked Emilia. She smiled and nodded.

It really was a thing of wonder: a private, isolated climate sealed off from the world, kept as cool as the dead of winter no matter where it was, and perfectly disguised at as a British Army uniform with gas mask.

“It took almost two years, but they finally perfected it,” she answered.

“Before Brigadier Halistone, the Colonel's late father, sent me to Eduardo Rosales, I had never seen very much of the outside world, save for what I read in books and heard on the radio,” Miller said. Lucky could tell Miller was smiling behind the mask. “Even though I cannot leave this suit, through it Emilia's father gave me freedom I had never experienced before.”

“Whenever my father stepped out to his workshop or to buy supplies, I'd put on my coat and sneak in. Miller taught me English, you know.”

“He's a good teacher,” Lucky said, recalling his brisk lesson with Miller aboard the Saint George about the history of the Office. The subject matter had been deadly serious then, so Miller was, too. It was funny to imagine a little girl sneaking past OCUO soldiers and into a giant freezer to play with him.

“Yes, little Miss Emmy and her brother would bring me books and stories of the outside world, and in turn I taught them what I could. I had never met a child other than the Colonel, when he was a young man, and I had never lived outside an icebox, not for as long as I could remember. The Rosales children and I had the insatiable curiosity for knowledge in common, and we all learned much while we lived together.”

Before Lucky could ask how Miller, who looked like he was only thirty, knew the Colonel, who had to be fifty, as a child, Emilia spoke up.

“He was a member of our family,” she said. She looked at the floor and added, “...Until you left.”

Her accusation hung in the air between them, trembling as if on threads.

“I had to go Emmy, my place was out in the world,” Miller said. Lucky could only see his eyes, but he looked stung. “I had taken your father away for too much of your childhood.”

“It didn't matter. Once you left, he left as well. He went all over the world, too.” Her eyes locked onto the red OCUO insignia on the gray-stained shoulder of Lucky’s uniform. “Your Office took him away, and he never spent more than a month with us before the end.”

“He was a great man, Emilia. And he was needed by people everywhere to build great and wonderful things. He wanted to make the world a better place for you and your brother.” His words seemed to dissipate in the dank air, not even reaching her. “Everything he did was for you.”

“It was his travels and friends that made the Francoists pay attention to him,” she whispered. “They called him ‘liberal educated elite.’ They called him many things and they arrested him. He never made it to the trial. He and my mother were taken by the mob. He was a scientist, she, a librarian. They called them witches as they burned.”

“Stop now, Emmy,” Miller whispered. He put his arm around her shoulders. Lucky watched in silence, again struck dumb. Her childhood, her family, had been cut short by fear, politics, and cruelty.

Pain that old and deep would always hurt like new, and it was never far from the surface. Lucky knew the feeling. He had many deaths on his conscience. Bucket stayed silent and seated. His boots dangled a couple inches above the dirt floor and he stared into the bottom of his empty orujo glass.

“You, and I, and Berto, and everyone who met him, knew your father led a good life, and that he loved you two and your mother more than anything in this world,” Miller whispered to her. “Everyone looked up to him because he lived by his principles. He did exactly what he said he would and helped countless people in doing so. Because he lived, the world was made a better place. What happened to him does not nullify the fact that he changed so many lives for the better.”

“That is what Berto and I wanted to do here, to help, and it has left me with nothing,” Emilia whispered. She looked like she wanted to sob, but no tears were forming in her green eyes.

A cheery bell rang out from the back corner of the cave.

Emilia was already on her feet, helmet on and both of her bladed revolvers in her hands, before Lucky recognized the sound of the alarm. The boulder guarding the entrance to this sanctuary was moving once more.

She dashed toward her wall of pull cords, ready to trigger the deadly traps she'd prepared for her pursuers.

Lucky drew his Colt .45, racked it back, then rushed after her.

Like what you read? Buy me a beer or @ me about it.

Copyright © 2023 Daniel Baldwin. All rights reserved.

Written and edited by Daniel Baldwin. Art by Dudu Torres. Spanish translations by Caitlin Gilmore.